I Got You

Saturday, June 13th, 2020I was speaking to a dear friend last night who had just come from her parents’ house on the corner of a street lined with tall sycamore and oak trees in Atlanta. The contents of the house were laid out on tables for an estate sale as the house is being sold. For more years than I can remember, I’ve called my friend just as she was getting ready to mow the large lawn for her parents. One day a week was devoted to that oversized lawn, and many more days to the help and care of aging parents who had now both passed away.

She was pulling into her own driveway when she said I’m about to cry and called you because I knew you would understand. I said it seems lately I fantasize too much about being a child again. The memories of wanting to flee my childhood and race towards adult notions have faded completely, and what remains is a certain longing to be a child again in my parents’ home.

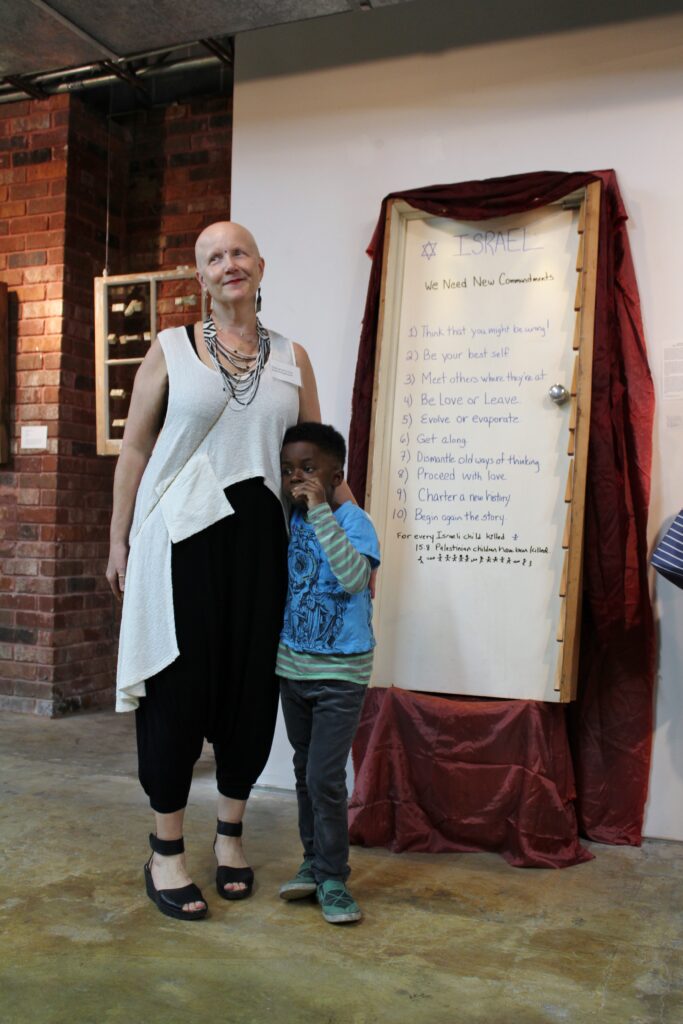

My friend asked how I was doing with everything going on and said she had seen me on television with the listening booths we had at the Hall. She said she liked my hat. I told her the truth – on any given day it’s hard to know where I’m at.

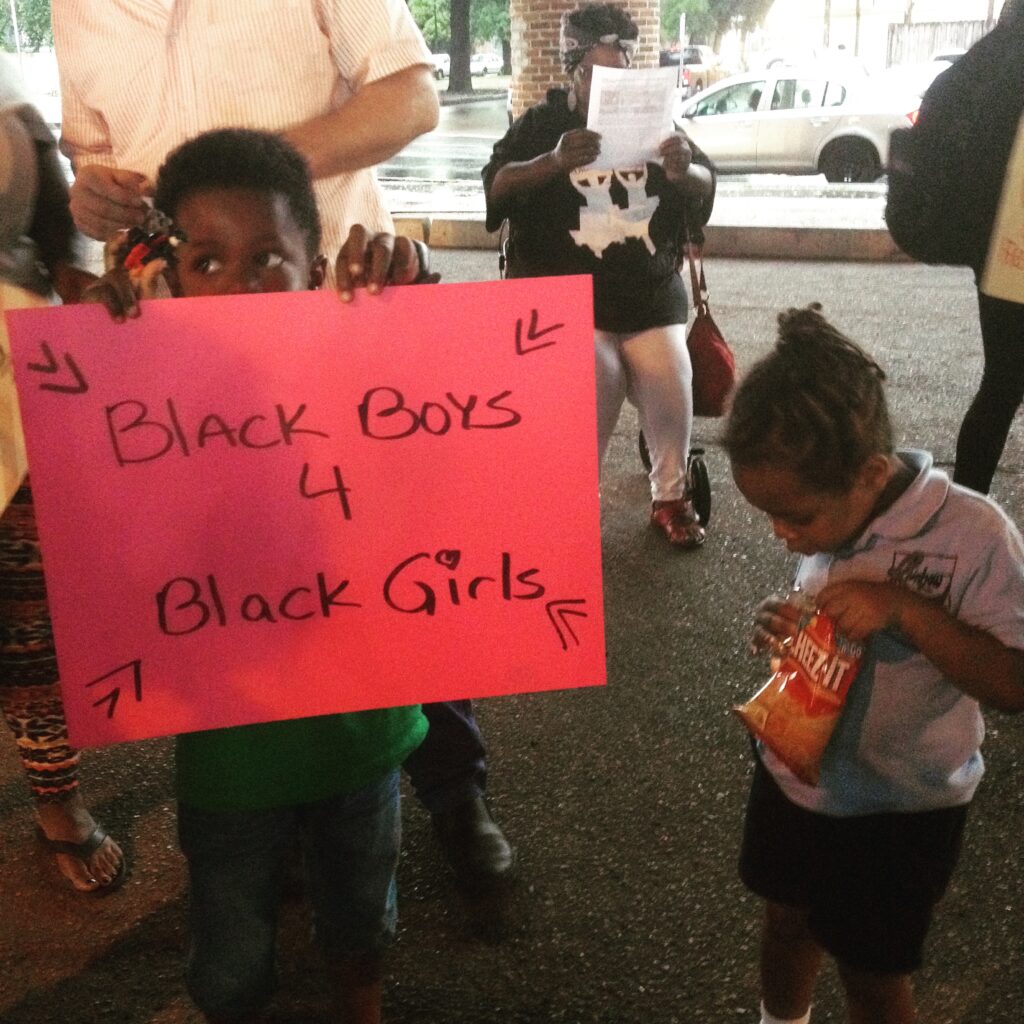

On Saturday, May 30th, Tin and I drove to Gulfport with friends to protest the killing of Black people. Again. This has become such a common thread for us that I don’t remember when we weren’t protesting. Tin’s comment when we got in the car, “Do we have to go to another protest?”

When Tin was young, I brooded about having to pierce the bubble of his innocent childhood with facts and fears about being a Black boy in America. I resented that my white friends didn’t mention Trayvon Martin to their three year olds; after all Tin and I had been to a rally, a teach in, a protest for the young 17-year-old Black boy murdered while holding a bag of Skittles. The gut wrenching knowledge that Trayvon’s murderer, George Zimmerman got off and went on to sign Skittle bags for white people as a memento is more than any of us should have to bear.

I’ve spoken on Department of Justice panels about community policing and listened to police chiefs talk about the implicit bias training and racial equity training they are undergoing and listen to them tell us how far we have come. And I respond the same way, every time. “When I have to tell my son that he risks being beaten up or killed by the police because he is Black, we have not come far enough.”

I have ended the day from workshops that I’ve led or workshops where I’ve participated in racial equity dialogues and have crawled deep in my couch trying to find space to believe in hope that my son stands a fighting chance in this country. I’ve fantasized about elsewhere and have traveled outside of America with my son to introduce him to the world in case he has to escape in order to breathe.

And though I’ve had the “talk” with my 11 year old about the police, though I’ve introduced him to resistance and resilience, my heart sank the other day when we were having a conversation at dinner. I said, “You never want to get yourself in a position where you have to even speak to the police. Do you understand?” And he said, “Is this about George Floyd?” I said this is about everything. It’s about a world that is upside down and you need to walk the straight and narrow so you don’t even have to have an encounter. Do you understand?

“I’m not worried,” Tin told me. “I got you.”

It was at that moment that I just wanted to walk off the planet with him in tow. Uh uh, I said, my lips trembling as I watched him put a mouthful of pasta into his mouth, you don’t got me. Red spaghetti sauce dotted his cheeks, his tee shirt, his placemat while his napkin was folded right beside his plate. I can’t do anything for you if you are out there by yourself. Do you understand? [I heard myself breathing as I spoke to him.] My whiteness is not going to help you if a police officer stops you and I’m not there.

I was mad, pissed, vexed, angry at him. At my son.

I realized everything I had taught Tin in the past eleven years was negated by what he sees. He sees my privilege. He sees my whiteness. He thinks his white mother makes him invincible. What a sorry ass thing to think. Did I contribute to this magical thinking on his part? What have I done to contribute to his naive feeling of safety.

This is what I was thinking at the dinner table with my 11-year-old son on a Thursday night: I was thinking oh no, don’t you feel safe, don’t you feel invincible, don’t you dare think I could help you. Because I can’t, God damn it all. I can’t do a bloody thing to help you survive in this world. I can’t protect you. Don’t sit here blissfully eating your spaghetti and tell me I got you, because I don’t got you son. I don’t got you.

Watch this if you think that any white mother could save her Black son. Or even a white friend save his Black friend.

What was your dinner conversation with your child last Thursday night?

Over and over and over again, I hear George Floyd call out for his mama. No MAMA – black, brown, red, yellow or white – can save her son from certain death at the hands of a system that supports mostly white men determined to destroy him.

Who was my 11-year-old self that I fantasize about returning to? My son does not get that. No, I’m not only stripping away his innocence, I’m already denying him a fantasy about his childhood when he gets older. Tell me this doesn’t suck. Then tell me what you plan to do about racism today?