The New York Times published an article about the best way to get over a breakup saying that writing and journaling is a healthy, productive tool.

Obviously, writing has been my tool, but in the public sphere of writing it is hard to really call out the one you are breaking up with on their behavior. You have to be sensitive to a public viewing. On the other hand, you also have your own portrayal of who you are in the whole unwinding.

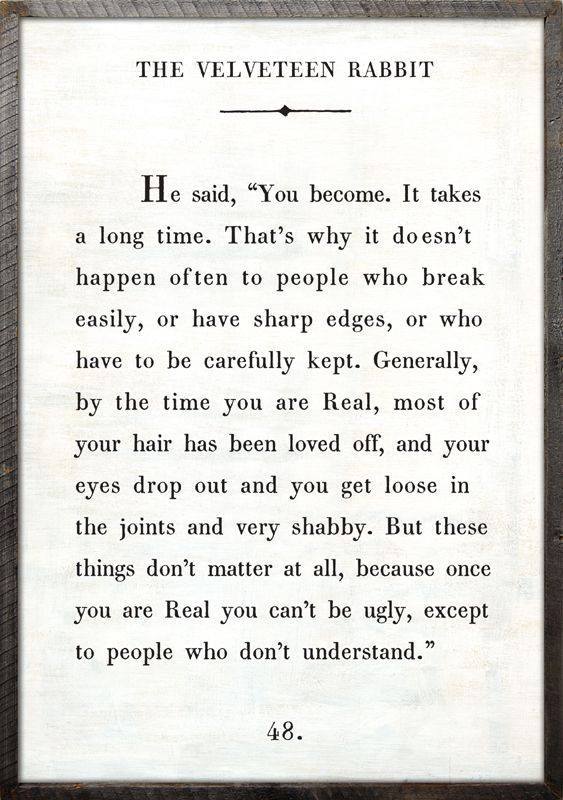

I’ve been honest to a fault at times and yet surprisingly tight-lipped in other areas. I think the thing about break-ups, any type, are that they are painful and yet provide endless self-revelation.

In my relationship with Sty, I didn’t realize how we went from a chance meeting to speaking several times a day, to planning future events, to engaging life philosophies into a single thought process. While it may have only been months of this, and while there had been flags I heeded, the unwinding or abrupt departure from this is just plain sad.

Maybe not sad in the way the ending of a 16-year relationship is, but sad in the hopes and dreams that are dashed when the promise of what’s to come suddenly dissipates.

The best way to get over a breakup is to suddenly be aware at how much this person’s presence had infiltrated your life and to now suddenly have that time made available to you again to do with what you choose. In one particularly painful break up, my therapist had asked me what I missed the most and I told her the witty and sexy text messages. She said find a friend who sends you witty text messages and engage them in repartee. It’s not the same, I said, because it does not hold the promise.

In Alain de Botton’s Essays in Love, he writes:

A long, gloomy tradition in Western thought argues that love is in its essence an unreciprocated, Marxist emotion and that desire can only thrive on the impossibility of mutuality. According to this view, love is simply a direction, not a place, and burns itself out with the attainment of its goal, the possession (in bed or otherwise) of the loved one. The whole of troubadour poetry of twelfth-century Provence was based on coital delay, the poet repeating his plaints to a woman who repeatedly declined a desperate gentleman’s offers. Centuries later, Montaigne declared that, ‘In love, there is nothing but a frantic desire for what flees from us’ – an idea echoed by Anatole France’s maxim that, ‘It is not customary to love what one has.’ Stendhal believed that love could be brought about only on the basis of a fear of losing the loved one and Denis de Rougemont confirmed, ‘The most serious obstruction is the one preferred above all. It is the one most suited to intensifying passion.’ To listen to this view, lovers cannot do anything save oscillate between the twin poles of yearning for someone and longing to be rid of them.

I don’t think it is unrequited love that turns us on, but instead the promise of tomorrow. Tomorrow is what makes today so exciting, without it, you return to living in the present, which we have all learned is where we need to be, but is often times, somewhat dull and routine for anyone with a romantic yearning. Oh yay, more work, oh yay, parenting, oh yay, the toilets need to be cleaned. Yes, you should turn to the bluebird whistling outside your window, but you are in the midst of a breakup and so I think a little wallowing is in order.

My brother has admonished me for being a romantic one too many times in my life. I guess, at this point, I will die a romantic. It is what it is.